Image 1027 – Whiting & Davis (not marked) regular flat mesh child’s purse – with finger ring and bell-shaped drop. Camel charm attached to front of mesh with jump ring. 1 ½ x 3 ½

Image 1027 – Whiting & Davis (not marked) regular flat mesh child’s purse – with finger ring and bell-shaped drop. Camel charm attached to front of mesh with jump ring. 1 ½ x 3 ½

Ever since ancient Egyptian culture captured the imagination of people the world over it has been a driving force in art and fashion. If you are among those beguiled by the ancient pharaohs perhaps you have contracted a touch of Egyptomania. Certainly the designers at Whiting & Davis and other mesh purse manufacturers were caught up in the craze.

Egyptomania is the abiding interest in the artifacts, architecture and culture of ancient Egypt held by people worldwide. This fascination is also sometimes referred to as Neo-Egyptian or Egyptian Revival. Some people think Egyptomania started in the United States in the 1920s after the discovery of King Tut’s tomb. In fact the phenomenon began in the ancient civilizations of Greece and Rome. Many of us are aware of Marc Antony and Caesar’s ill-fated obsessions with Egypt. In the early 1800s Napoleon was so infatuated with Egyptian antiquity that he arrived with a team of 150 experts called “savants,” who were charged with studying, cataloging and mapping as many ancient artifacts as they could find. The British arrived in 1882 followed by the Americans.

Luxor Temple founded in 1392 BC. One of the two original obelisks flanking the entrance still stands. The other obelisk is now in the Place de la Concorde in Paris.

It seems that the goal of every country possessed by Egyptomania was to transport one of Egypt’s giant obelisks back home. One of these massive stone monuments with ancient carved hieroglyphs that was originally brought to Rome in 37 AD was moved to its present Vatican City location in front of St. Peter’s Basilica in 1586. This still left Rome with no less than eight ancient Egyptian obelisks, a testament to the degree of the Roman obsession. In the nineteenth century three ancient Egyptian obelisks, popularly dubbed Cleopatra’s Needles, were moved to Paris, London and New York City. Ironically none of these three monuments has anything to do with Cleopatra. France received her obelisk, known as the Luxor obelisk, in 1833. England finally landed hers in 1877 after nearly losing it at sea, though it wasn’t erected until 1878 after some wrangling over the best venue for it. The New York City needle was gifted by Egypt in 1877 and erected in Central Park in 1881. Egyptomania ran rampant in every location where an obelisk was installed.

R. Blackinton & Co. (N. Attleboro, MA) sterling silver ring mesh purse – frame featuring winged Egyptian figures and lotus blossoms. Stamped inside frame, “B” with sword through it (maker’s mark used until 1912). Frame also marked “Sterling” and “3320” (pattern number). 6 x 5 ¼ (Image courtesy of Jennifer Whitehair)

In early November 1922 British archaeologist Howard Carter was elated when his excavation team found a stairway cut into the bedrock in the Valley of the Kings near Luxor in central Egypt. With his wealthy patron, Earl of Carnarvon, at his side, Carter finally chiseled a small opening in the door of the antechamber of King Tutankhuman’s tomb on November 26th and peered in to discover objects unseen for the past 3,200 years. Inserting a candle into the darkness Carter stared in awe at the sentinel statues guarding the still-sealed door to the burial chamber, as well as funerary objects made of gold and ebony. When asked by Carnarvon if he could see anything Carter replied with the now famous pronouncement, “Yes, wonderful things.”

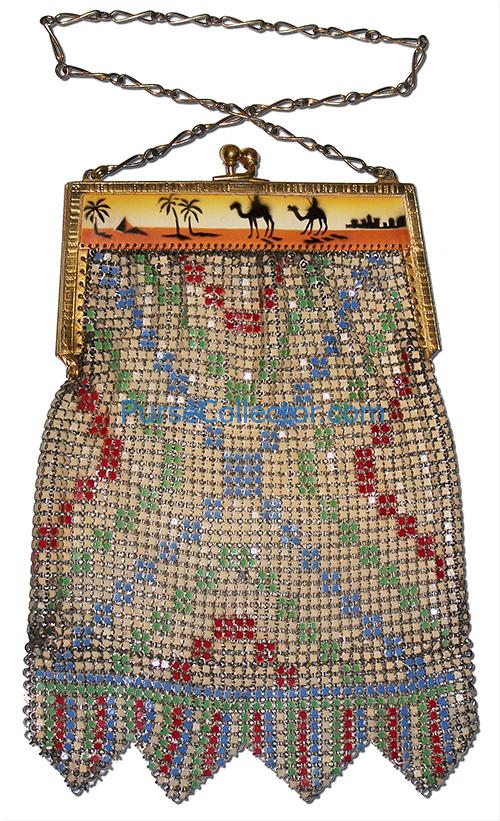

Whiting & Davis regular flat mesh purse – frame painted on front with scene showing palm trees, pyramids, camels with riders, and desert city. Metal tag stamped with W&D logo attached to inside of frame by spiral wire. 4 x 6 ½ (Image courtesy of Ellen Mansoor Collier)

The news of Carter’s discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb set off a tidal wave of Egyptomania that swept round the world. From that point through the end of 1926 Egyptian influences pervaded modern culture in the United States to a level not previously experienced. Egyptian motifs became an integral part of the Art Deco movement, a style that dominated decorative arts through the end of the decade and beyond. Clearing and documenting King Tut’s tomb continued through 1932, but Carter took a hiatus from archaeology shortly after opening the sealed burial chamber in February 1923. In 1924 Carter visited the United States giving a series of illustrated lectures that were enthusiastically received. His visit served to stoke the fires of Egyptomania and raise the collective consciousness to new heights.

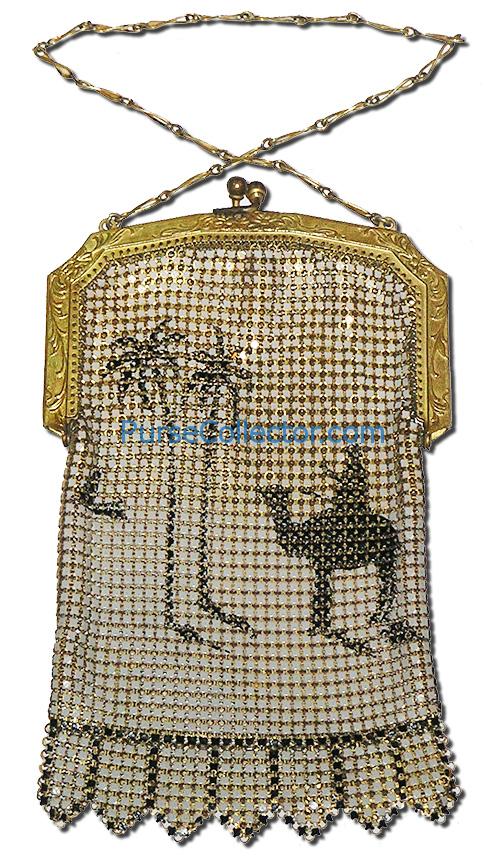

Whiting & Davis (not marked) regular flat mesh purse – scene showing two camels with riders. 4 7/8 x 7 1/8 (Image courtesy of Ellen Mansoor Collier)

Image 1029 – Whiting & Davis (not marked) regular flat mesh child’s purse – palm tree and minaret design. Checkerboard painted frame. 2 ¼ x 3 ½

In the 1920s Whiting & Davis, unlike its major competitor, Mandalian Mfg., was a company that tracked and capitalized on popular culture. Its leaders were as attuned to what was trending as any Twitter acolyte is today. World’s fairs, soft drinks and characters from children’s books and cartoons were all subjects of designs on W&D mesh purses of the era. The minutest details of Carter’s discoveries were painstakingly reported daily in the press and his lectures were front page news in major cities across the U.S. W&D managers undoubtedly kept abreast of every new development just like people did all over the country and throughout the world.

Whiting & Davis (not marked) regular flat mesh purse – desert scene viewed through an open window. 5 1/8 x 7 (Image courtesy of Jennifer Whitehair)

The New York Times of March 23, 1923 reported that the U.S. Patent Office in Washington D.C. received a flood of applications for the use of Tut-Ankh-Amen as a trademark for objects primarily for “women’s use.” Dress styles were among the many fashion influences shaped by King Tut’s “arrival.” Prints, some of which were exceedingly bright and vivid, portrayed Egyptian scenes replete with patterns of camels, sphinxes and palm trees according to a 1923 Art and Archaeology magazine article.

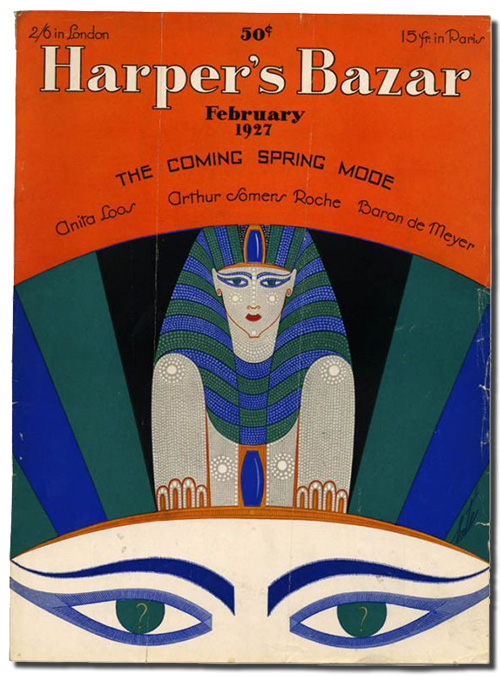

Harper’s Bazar magazine for February 1927 announcing “the coming spring mode” of fashion on an Egyptian Revival, Art Deco cover.

In addition there were Tiffany scarab brooches and Cartier bracelets with Egyptian figures created in diamonds and rubies. Products from cigarettes to typewriters to soap were also being promoted through references to Egyptian themes. And of course movies about ancient Egypt powered Egyptomania in popular culture and contributed to women’s desire to possess all things Egyptian. Even after interest in Egyptian-themed fashions had waned Hollywood released the Boris Karloff film “The Mummy” (1932) and the Cecil B. DeMille production “Cleopatra” (1934), starring Claudette Colbert. Whiting & Davis supplied mesh for some of the costumes for “Cleopatra,” including one for Colbert’s co-star Henry Wilcoxen who played the role of Marc Antony.

Henry Wilcoxon as Marc Antony and Claudette Colbert as Cleopatra in the 1934 Cecil B. DeMille film “Cleopatra.” Marc Antony is wearing W&D mesh.

When attempting to date mesh purses with Egyptian themes it is important to understand that W&D didn’t start selling flat mesh bags with painted designs on the mesh until 1924. The first painted mesh bags featured very basic geometric designs.

Whiting & Davis regular flat mesh purse – camel in an oval vignette painted on goldtone mesh. W&D logo stamped on inside of frame. 4 x 7 (Image courtesy of Ellen Mansoor Collier)

With improvements in stencil design and painting techniques came more elaborate designs on mesh bags produced in a broader array of colors. In 1927 painted Dresden mesh (fine ring mesh) bags were introduced. Art Deco geometrics and Art Nouveau florals were common themes for painted mesh designs, but as technology improved scenic designs portraying landscapes, people, birds, and animals appeared. Notice that all of the W&D flat mesh bags shown in this article are made from the original-style armor mesh rather than Ivorytone mesh that came on the scene around 1930-31. This observation tells us that the bags were probably all made between 1924 and 1930, which makes perfect sense given the enthusiasm for Egyptian design that shaped the fashion industry during a portion of this period of time.

Image 1025 – Whiting & Davis regular flat mesh purse – black on white silhouettes painted on mesh. Metal tag stamped with W&D logo attached to inside of frame by spiral wire. 3 ¾ x 6

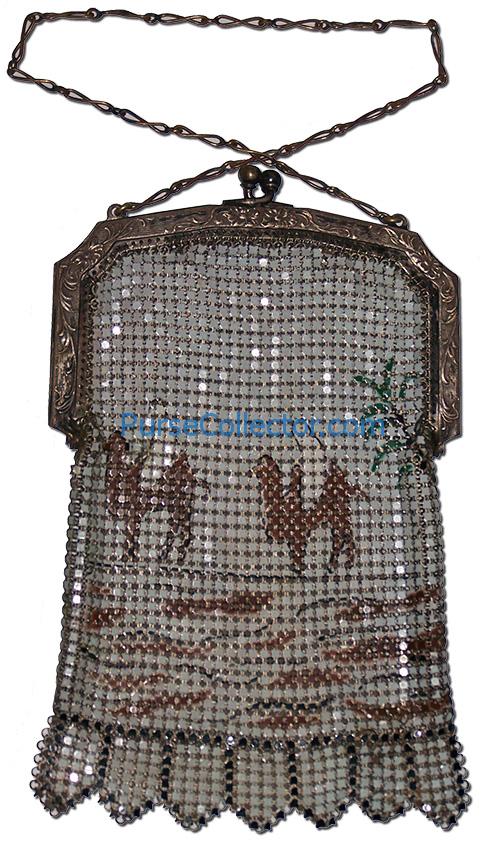

Whiting & Davis (not marked) regular flat mesh purse – scene showing two camels with riders. 3 5/8 x 5 5/8 (Image courtesy of Ellen Mansoor Collier)

Certain designs on mesh purses were obviously influenced by Egyptian Revival sentiment in the late 1920s. Images of pyramids, palm trees and camels, some with robed Arab riders, were all found on mesh bags of this period. The lotus blossom design, however, represents a subtle Egyptian theme that some collectors might not perceive as Egyptomania-inspired.

Image 1028 – Whiting & Davis regular flat mesh purse – lotus blossom design on pale green background. W&D logo stamped on inside of both sides of frame. 4 ¼ x 6 ½

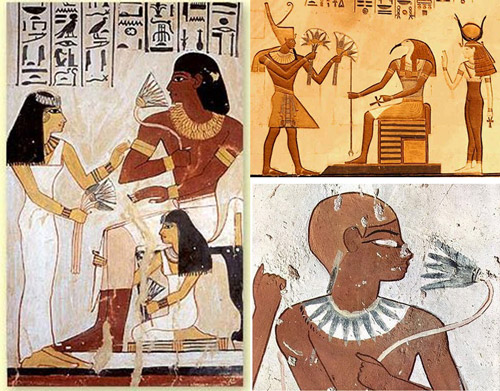

Ancient Egyptian priests observed lotus plants retracting below a pond’s surface at night, re-emerging in the morning and blooming during the day. They associated these events with both human resurrection and the daily disappearance and reappearance of the sun. The famous Egyptian “Book of the Dead” included spells to transform a person into a lotus thus allowing for rebirth. The lotus evolved as a very important symbol in the religious art of ancient Egypt and became an iconic design found on a W&D mesh bag made in the late 1920s.

Examples of the use of lotus images in ancient Egyptian art.

Even before Carter’s documentation of the artifacts from King Tut’s tomb was completed in 1932, the fashion world had embraced other interests. However, Whiting & Davis left a legacy of fascinating scenic and figural purses from the preceding years that mesh purse collectors now covet as artifacts of the Art Deco period. And although finding an Egyptian-themed mesh purse doesn’t compare to Carter’s discovery, today’s collectors definitely experience a thrill … and perhaps a little twinge of Egyptomania … upon unearthing one of these “wonderful things.”